"What if?" Scenario analysis in the CPU Window

Brian Long - 29/Oct/2017

Brian Long - 29/Oct/2017

[SHOWTOGROUPS=4,20]

Last Tuesday, 24th October I did some sessions at EKON 21, one of which was on Creative Debugging Techniques. During the session there was a section where I was trying to demonstrate an idea or technique that happened to fully involve the CPU window. Unfortunately a series of finger fumbles on my part meant I couldn’t show what I wanted to show, albeit I think the point was made.

Anyway, I mentioned that maybe I’d write up that little snippet into a blog post, just to prove that it really does work as I suggested it does, and so here it is.

Oh, apologies up front for all the animated GIFs below- it seemed the most expeditious way to make sure I could really convey some of the points.

So the context was ‘What if?’ situations and testing out such scenarios during a debug session.

Clearly the primary tool for testing out ‘What if?’ scenarios is the Run, Evaluate/Modify… (Ctrl+F7) dialog. This dialog’s Modify button allows you to alter the value of the expression you have evaluated to find out how code behaves when the expression has a value other than what it actually had.

That’s a good and very valuable tool. But the case in point in the EKON 21 session was a bit different.

Consider a scenario where you are in the midst of a lengthy debug session, one that you’d really rather not reset and start again. Also consider that from some observations made in the debug session you have realised that a certain function B that is called from function A ought in fact not to be called. You want to test how well things pan out with B not being called.

In an entirely fabricated ultra-academic example, let’s use this code here, where A is TMainForm.WhatIfButtonClick and B is CommonRoutine.

One solution to this is to move the instruction pointer to skip the call to B just as B is about to be called. This can be done in a number of ways in Delphi. Set a breakpoint on the call to B and when it hits do one of the following four options to achieve this:

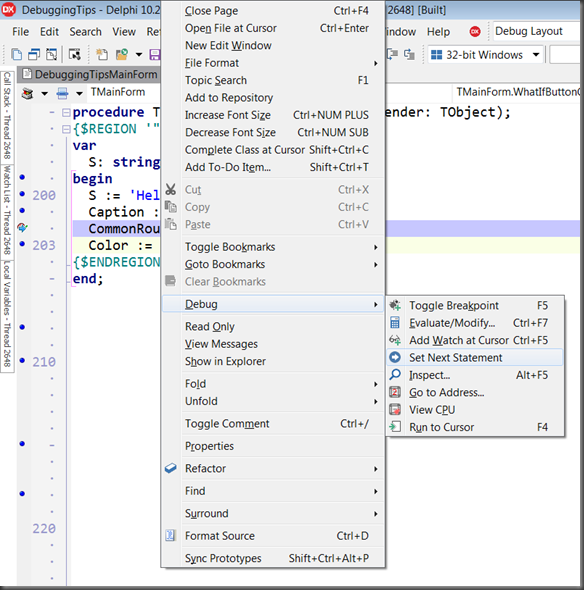

1) Set next statement menu item

Right-click on the statement that follows the call to B and select Debug, Set Next Statement, a menu item added in Delphi 2006 and described by Chris Hesik in this old 2007 blog post (from the Internet Archive WayBack Machine).

2) Drag the instruction pointer editor gutter icon

Drag the instruction pointer icon in the editor gutter to point at the following statement. This drag and drop support for the instruction pointer symbol was added in Delphi 2010.

3) Change the instruction pointer in the CPU window

Invoke the CPU window (View, Debug Windows, CPU Windows, Entire CPU or Ctrl+Alt+C), or at the very least the Disassembly pane (View, Debug Windows, CPU Windows, Disassembly or Ctrl+Alt+D). Right click on the next statement and choose New EIP (or Ctrl+N).

4) Update the EIP register in the CPU window

Invoke the CPU window (View, Debug Windows, CPU Windows, Entire CPU or Ctrl+Alt+C). Note the address of the instruction you want to execute next. Right-click the EIP register in the Registers pane and choose Change Register… (Ctrl+H) and enter the new value as a hexadecimal number, i.e. with a $ prefix. An alternative to Change Register… is to choose Increment Register (Ctrl+I) a sufficient number of times to get the value to match the target address.

OK, so all of those achieve the goal on that single invocation of routine A, but what about the case where A is called lots of times – lots and lots of times? This idea falls down in that situation and so we might seek out an alternative option.

Maybe we can get rid of the call to B entirely for this run of the executable. Yes, maybe we can and indeed that was just the very technique I tried to show, but made a couple of silly mistakes by not paying attention to what exactly was on the screen. Mea culpa.

There are a couple of approaches to getting rid of the call to B from the code present in A. One is to replace the first few bytes of that statement with an instruction that jumps to the next statement. The other is to replace the entire statement with opcodes corresponding to ‘no operation’, i.e. the no-op opcode NOP. Let’s look at both approaches.

Both these approaches involve changing existing machine instructions in memory. With that end goal comes a rule, and the rule is that you can’t successfully change a machine instruction that your program is currently stopped at in the debugger or that the debugger has a breakpoint on. In other words, if you want to change the call to CommonRoutine to be something else this must be done when the program is stopped at a different instruction in the debugger and there must be no breakpoint on that instruction.

This is simply a side effect of the way debuggers implement breakpoints and statement stepping - they replace the first byte of the instruction to break at with $CC, the byte value, or opcode, for the assembly instruction INT 3. When execution continues the $CC is swapped back for the original value.

So if you change the instruction at the current EIP when the execution has stopped in the debugger, when you ask it to move on your first byte will get replaced, just by the mechanics of your debugger doing its day job. This will most likely cause a very much unwanted opcode combination leading quickly to an application crash. [ One of my EKON fumbles was to instantly forget this previously well known (by me) fact and promptly get a crashed debuggee. ]

Your best bet is to put a breakpoint on the preceding instruction, and then modify/replace your target instruction. Make sure there is no breakpoint on the target instruction.

When you look in the CPU window you can see the assembly instructions that correspond to the Pascal statement above it.

In the case of the call to CommonRoutine the assembly code is:

The machine code bytes (opcodes) that represent those 2 instructions are $8B, $45, $FC and $E8, $11, $F8, $FF, $FF respectively. The 3 bytes for the first instruction are stored at locations starting at $5D1287 and the 5 bytes for the second instruction start at $5D128A.

The statement following the call to CommonRoutine starts at address $5D128F, 8 bytes on from $5D1287.

[/SHOWTOGROUPS]

Last Tuesday, 24th October I did some sessions at EKON 21, one of which was on Creative Debugging Techniques. During the session there was a section where I was trying to demonstrate an idea or technique that happened to fully involve the CPU window. Unfortunately a series of finger fumbles on my part meant I couldn’t show what I wanted to show, albeit I think the point was made.

Anyway, I mentioned that maybe I’d write up that little snippet into a blog post, just to prove that it really does work as I suggested it does, and so here it is.

Oh, apologies up front for all the animated GIFs below- it seemed the most expeditious way to make sure I could really convey some of the points.

So the context was ‘What if?’ situations and testing out such scenarios during a debug session.

Clearly the primary tool for testing out ‘What if?’ scenarios is the Run, Evaluate/Modify… (Ctrl+F7) dialog. This dialog’s Modify button allows you to alter the value of the expression you have evaluated to find out how code behaves when the expression has a value other than what it actually had.

That’s a good and very valuable tool. But the case in point in the EKON 21 session was a bit different.

Consider a scenario where you are in the midst of a lengthy debug session, one that you’d really rather not reset and start again. Also consider that from some observations made in the debug session you have realised that a certain function B that is called from function A ought in fact not to be called. You want to test how well things pan out with B not being called.

In an entirely fabricated ultra-academic example, let’s use this code here, where A is TMainForm.WhatIfButtonClick and B is CommonRoutine.

Код:

procedure TMainForm.WhatIfButtonClick(Sender: TObject);

{$REGION '"What if?" scenarios'}

var

S: string;

begin

S := 'Hello world';

Caption := S;

CommonRoutine;

Color := Random($1000000);

{$ENDREGION}

end;1) Set next statement menu item

Right-click on the statement that follows the call to B and select Debug, Set Next Statement, a menu item added in Delphi 2006 and described by Chris Hesik in this old 2007 blog post (from the Internet Archive WayBack Machine).

2) Drag the instruction pointer editor gutter icon

Drag the instruction pointer icon in the editor gutter to point at the following statement. This drag and drop support for the instruction pointer symbol was added in Delphi 2010.

3) Change the instruction pointer in the CPU window

Invoke the CPU window (View, Debug Windows, CPU Windows, Entire CPU or Ctrl+Alt+C), or at the very least the Disassembly pane (View, Debug Windows, CPU Windows, Disassembly or Ctrl+Alt+D). Right click on the next statement and choose New EIP (or Ctrl+N).

4) Update the EIP register in the CPU window

Invoke the CPU window (View, Debug Windows, CPU Windows, Entire CPU or Ctrl+Alt+C). Note the address of the instruction you want to execute next. Right-click the EIP register in the Registers pane and choose Change Register… (Ctrl+H) and enter the new value as a hexadecimal number, i.e. with a $ prefix. An alternative to Change Register… is to choose Increment Register (Ctrl+I) a sufficient number of times to get the value to match the target address.

OK, so all of those achieve the goal on that single invocation of routine A, but what about the case where A is called lots of times – lots and lots of times? This idea falls down in that situation and so we might seek out an alternative option.

Maybe we can get rid of the call to B entirely for this run of the executable. Yes, maybe we can and indeed that was just the very technique I tried to show, but made a couple of silly mistakes by not paying attention to what exactly was on the screen. Mea culpa.

There are a couple of approaches to getting rid of the call to B from the code present in A. One is to replace the first few bytes of that statement with an instruction that jumps to the next statement. The other is to replace the entire statement with opcodes corresponding to ‘no operation’, i.e. the no-op opcode NOP. Let’s look at both approaches.

Both these approaches involve changing existing machine instructions in memory. With that end goal comes a rule, and the rule is that you can’t successfully change a machine instruction that your program is currently stopped at in the debugger or that the debugger has a breakpoint on. In other words, if you want to change the call to CommonRoutine to be something else this must be done when the program is stopped at a different instruction in the debugger and there must be no breakpoint on that instruction.

This is simply a side effect of the way debuggers implement breakpoints and statement stepping - they replace the first byte of the instruction to break at with $CC, the byte value, or opcode, for the assembly instruction INT 3. When execution continues the $CC is swapped back for the original value.

So if you change the instruction at the current EIP when the execution has stopped in the debugger, when you ask it to move on your first byte will get replaced, just by the mechanics of your debugger doing its day job. This will most likely cause a very much unwanted opcode combination leading quickly to an application crash. [ One of my EKON fumbles was to instantly forget this previously well known (by me) fact and promptly get a crashed debuggee. ]

Your best bet is to put a breakpoint on the preceding instruction, and then modify/replace your target instruction. Make sure there is no breakpoint on the target instruction.

When you look in the CPU window you can see the assembly instructions that correspond to the Pascal statement above it.

In the case of the call to CommonRoutine the assembly code is:

Код:

mov eax,[ebp-$04]

call TMainForm.CommonRoutineThe statement following the call to CommonRoutine starts at address $5D128F, 8 bytes on from $5D1287.

[/SHOWTOGROUPS]